Quando l’opera smette di essere materia

Nel momento esatto in cui la mano dell’artista incontra il supporto, accade qualcosa che va oltre la materia. Il gesto non è più solo un mezzo tecnico, ma diventa un atto fondativo: è lì che l’opera nasce davvero. Prima ancora della forma, prima dell’immagine riconoscibile o del risultato finale, esiste un istante irripetibile in cui intenzione, corpo e pensiero coincidono. È in quel punto che l’arte smette di essere semplice oggetto e diventa esperienza.

Nel corso della storia dell’arte, il gesto ha assunto ruoli diversi: narrativo, simbolico, distruttivo, liberatorio. Ma ciò che rimane costante è la sua natura non replicabile. Anche quando l’opera sembra seriale o ripetibile, il gesto che la origina resta unico. Ed è proprio questa unicità a rendere il gesto uno dei cardini sia della lettura critica sia della tutela di mercato.

Il passaggio chiave: l’intenzionalità

Parlare di gesto, oggi, senza introdurre il concetto di intenzionalità, sarebbe riduttivo. Il gesto artistico non è mai casuale, nemmeno quando appare istintivo o automatico. È sempre il risultato di una scelta, conscia o inconscia, che avviene all’interno di un sistema culturale, storico e personale.

L’intenzionalità distingue il gesto artistico dal movimento meccanico. Un segno tracciato senza intenzione resta un segno; un segno carico di intenzione diventa linguaggio. In questo senso, il gesto è una dichiarazione: afferma una visione del mondo, un rapporto con la tradizione, una presa di posizione rispetto al presente.

L’arte del Novecento ha reso esplicito questo passaggio. Quando l’opera smette di rappresentare qualcosa e inizia a essere qualcosa, il gesto assume un valore autonomo. Non serve più “mostrare”: basta agire.

Caravaggio: il gesto come verità incarnata

Nel lavoro di Caravaggio, il gesto è già rottura. Non è un gesto astratto, ma profondamente fisico e umano. Le mani che emergono dal buio, i corpi colti nell’istante della massima tensione, le posture teatrali ma mai idealizzate: tutto nasce da una pittura che è azione diretta sulla realtà.

Caravaggio non costruisce le figure, le afferra. Il suo gesto pittorico coincide con un atto di presa sul reale, spesso brutale, sempre intenzionale. Non c’è decorazione, non c’è distanza: il segno segue il corpo, lo asseconda, lo incide. È un gesto che fonda una nuova idea di verità pittorica, dove l’opera non sublima il mondo ma lo espone.

Fontana: il gesto che supera la materia

Con Lucio Fontana il gesto compie un salto radicale. Il taglio non è un effetto, ma l’opera stessa. Non rappresenta, non descrive: accade. Il gesto di incidere la tela è un atto definitivo, irreversibile, che trasforma la superficie pittorica in spazio reale.

Qui l’intenzionalità è assoluta. Ogni taglio è unico, non perché non possa essere imitato, ma perché nessuna imitazione potrà mai coincidere con quell’atto preciso, compiuto in un tempo e in un luogo determinati. Il gesto di Fontana è fondativo perché ridefinisce cosa può essere un’opera d’arte: non più un’immagine, ma un evento.

Schifano: il gesto come velocità e stratificazione

In Mario Schifano il gesto torna a essere pittura, ma una pittura attraversata dai media, dalla ripetizione, dalla cultura visiva contemporanea. Il segno è rapido, spesso apparentemente disordinato, ma sempre carico di intenzione.

Schifano lavora per stratificazioni, cancellazioni, ritorni. Il gesto non è mai definitivo, ma accumulativo. Ogni intervento dialoga con ciò che lo precede, creando una tensione continua tra controllo e abbandono. Anche qui, ciò che conta non è il soggetto, ma il modo in cui il gesto lo attraversa e lo trasforma.

Antonio Sanfilippo: il gesto come struttura mentale

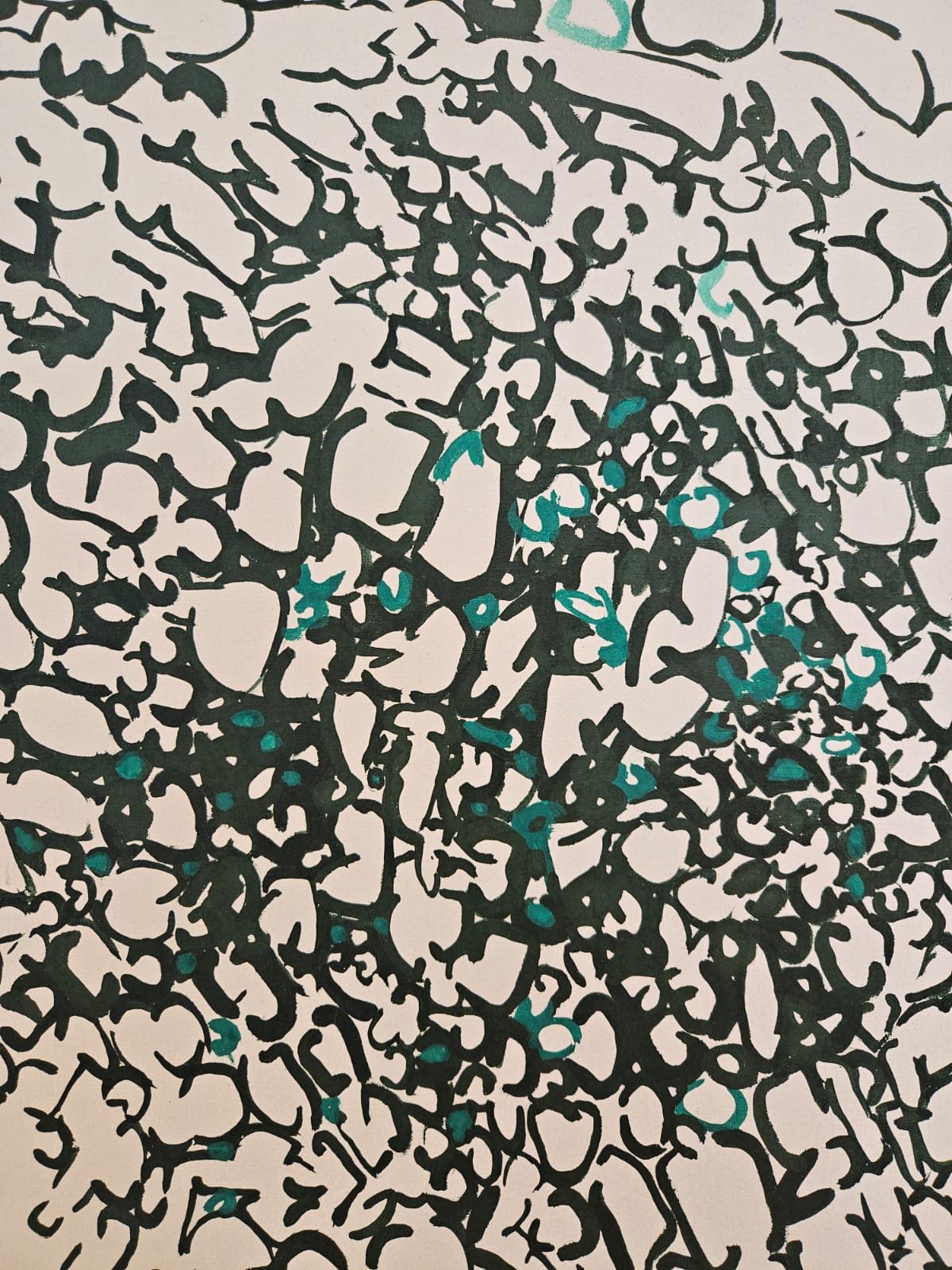

All’interno di questo percorso, l’opera di Antonio Sanfilippo rappresenta un passaggio cruciale e spesso sottovalutato. Sanfilippo non lavora sul gesto come esplosione o rottura, ma come costruzione di un sistema segnico coerente e rigoroso.

Nelle sue opere degli anni Sessanta, il segno si moltiplica, si ripete, si organizza in costellazioni che sembrano crescere organicamente sulla superficie. Il gesto è controllato, ma non freddo; è ripetuto, ma mai identico. Ogni segno nasce da un’intenzionalità precisa, ma lascia spazio a variazioni minime che rendono l’opera viva.

Nel lavoro di Sanfilippo, il gesto diventa pensiero visibile. Non è l’espressione di un’emozione immediata, ma il risultato di una riflessione profonda sul linguaggio della pittura. È proprio questa tensione tra ripetizione e unicità a rendere il suo gesto non replicabile: anche quando il vocabolario segnico è riconoscibile, l’opera resta irriducibile a una formula.

Il gesto come ciò che non è replicabile

In un’epoca di riproducibilità tecnica e di immagini infinite, il gesto artistico rimane uno degli ultimi territori dell’unicità. Si possono copiare le forme, imitare gli stili, simulare i processi. Ma il gesto originario – quello che nasce dall’incontro tra un artista e un’opera – non è trasferibile.

Questa non replicabilità non è solo materiale, ma temporale e intenzionale. Anche lo stesso artista, ripetendo un gesto simile, non potrà mai ricreare le condizioni identiche del primo atto. Cambiano il tempo, il contesto, lo stato mentale. Il gesto è sempre situato.

È per questo che, nel collezionismo consapevole, il valore di un’opera non risiede solo nella sua apparenza, ma nella sua origine. Possedere un’opera significa entrare in relazione con un gesto avvenuto una sola volta.

Perché il mercato tutela il gesto

Il mercato dell’arte, spesso percepito come distante dalla dimensione poetica, è in realtà uno dei principali custodi del gesto artistico. Autentiche, archivi, provenienze non sono meri strumenti burocratici, ma dispositivi di tutela dell’intenzionalità.

Un certificato di autenticità non garantisce solo che un’opera sia “vera”: garantisce che quel gesto è riconducibile a un artista specifico, in un momento preciso della sua ricerca. Gli archivi non conservano solo immagini, ma tracciano continuità e rotture all’interno di un percorso creativo. La provenienza racconta la storia di come quel gesto è stato riconosciuto, custodito, trasmesso.

In questo senso, il mercato non protegge la materia, ma l’atto. Tutela la possibilità, per chi guarda oggi, di entrare in contatto diretto con un gesto che appartiene al passato ma continua ad agire nel presente.

Un invito allo sguardo lento

Riconoscere il gesto significa rallentare. Significa guardare un’opera non per ciò che rappresenta, ma per ciò che è accaduto per renderla possibile. In un tempo dominato dalla velocità e dalla superficie, il gesto artistico ci chiede attenzione, ascolto, rispetto.

Nel Journal di Luma Arte Contemporanea, questo spazio è dedicato proprio a questo: restituire profondità allo sguardo, offrire strumenti per leggere l’arte oltre l’immagine, riportando al centro ciò che davvero conta – l’atto intenzionale che trasforma la materia in opera.

Questo testo si inserisce in un percorso di riflessione più ampio sul linguaggio dell’arte e sulla costruzione del senso nell’opera contemporanea. Per approfondire ulteriormente questi temi, è possibile rileggere l’articolo precedente del Journal, che ne costituisce il naturale punto di partenza.

Se desideri approfondire questi temi attraverso opere storicizzate e lavori disponibili in galleria, ti invitiamo a esplorare le opere selezionate su Luma Arte Contemporanea.

Ogni opera è un gesto che continua a parlare: sta a noi imparare ad ascoltarlo.

The artist’s gesture

When the artwork ceases to be matter

At the precise moment when the artist’s hand meets the surface, something happens that goes beyond matter. The gesture is no longer merely a technical means; it becomes a founding act. It is there that the artwork truly comes into being. Before form, before any recognizable image or final result, there is an unrepeatable instant in which intention, body, and thought coincide. At that point, art ceases to be a simple object and becomes an experience.

Throughout the history of art, the gesture has taken on different roles: narrative, symbolic, destructive, liberating. Yet one element remains constant—its irreducible uniqueness. Even when an artwork appears serial or repeatable, the gesture that generated it remains singular. It is precisely this uniqueness that makes the gesture one of the key pillars of both critical interpretation and market protection.

The key passage: intentionality

To speak of gesture today without introducing the concept of intentionality would be reductive. The artistic gesture is never accidental, not even when it appears instinctive or automatic. It is always the result of a choice—conscious or unconscious—made within a cultural, historical, and personal framework.

Intentionality distinguishes the artistic gesture from mechanical movement. A mark made without intention remains a mark; a mark charged with intention becomes language. In this sense, the gesture is a declaration: it affirms a worldview, a relationship with tradition, a position within the present.

Twentieth-century art made this passage explicit. When the artwork stops representing something and begins to be something, the gesture acquires autonomous value. There is no longer a need to “show”: it is enough to act.

Caravaggio: gesture as embodied truth

In the work of Caravaggio, gesture already represents rupture. It is not an abstract gesture, but a profoundly physical and human one. Hands emerging from darkness, bodies caught at the peak of tension, theatrical yet never idealized postures: everything originates from a painting that acts directly upon reality.

Caravaggio does not construct figures—he seizes them. His painterly gesture coincides with an act of grasping the real, often brutal, always intentional. There is no decoration, no distance: the mark follows the body, responds to it, engraves it. It is a gesture that founds a new idea of pictorial truth, in which the artwork does not sublimate the world but exposes it.

Fontana: the gesture that transcends matter

With Lucio Fontana, the gesture makes a radical leap. The cut is not an effect; it is the artwork itself. It does not represent, it does not describe—it happens. The act of cutting the canvas is a definitive, irreversible gesture that transforms the pictorial surface into real space.

Here, intentionality is absolute. Each cut is unique, not because it cannot be imitated, but because no imitation can ever coincide with that precise act, carried out at a specific time and place. Fontana’s gesture is founding because it redefines what an artwork can be: no longer an image, but an event.

Schifano: gesture as speed and stratification

In Mario Schifano, the gesture returns to painting, yet a painting permeated by media, repetition, and contemporary visual culture. The mark is rapid, often seemingly disordered, but always charged with intention.

Schifano works through layers, erasures, returns. The gesture is never definitive, but accumulative. Each intervention enters into dialogue with what precedes it, creating a constant tension between control and abandonment. Here too, what matters is not the subject, but the way the gesture traverses and transforms it.

Antonio Sanfilippo: gesture as mental structure

Within this trajectory, the work of Antonio Sanfilippo represents a crucial and often underestimated passage. Sanfilippo does not approach gesture as explosion or rupture, but as the construction of a coherent and rigorous sign system.

In his works from the 1960s, the sign multiplies, repeats, and organizes itself into constellations that seem to grow organically across the surface. The gesture is controlled, yet not cold; repeated, yet never identical. Each mark is born of a precise intentionality, while leaving room for minimal variations that keep the work alive.

In Sanfilippo’s practice, the gesture becomes visible thought. It is not the expression of an immediate emotion, but the result of deep reflection on the language of painting. It is precisely this tension between repetition and uniqueness that renders his gesture non-replicable: even when the sign vocabulary is recognizable, the artwork remains irreducible to a formula.

The gesture as what cannot be replicated

In an age of technical reproducibility and infinite images, the artistic gesture remains one of the last territories of uniqueness. Forms can be copied, styles imitated, processes simulated. But the original gesture—the one born from the encounter between an artist and an artwork—cannot be transferred.

This non-replicability is not only material, but temporal and intentional. Even the same artist, repeating a similar gesture, can never recreate the identical conditions of the first act. Time changes, context changes, the mental state changes. The gesture is always situated.

For this reason, in informed collecting, the value of an artwork does not lie solely in its appearance, but in its origin. To own an artwork means to enter into a relationship with a gesture that occurred once and only once.

Why the market protects the gesture

The art market, often perceived as distant from the poetic dimension, is in fact one of the primary custodians of the artistic gesture. Certificates of authenticity, archives, and provenance are not mere bureaucratic tools, but mechanisms for safeguarding intentionality.

A certificate of authenticity does not simply guarantee that an artwork is “real”: it guarantees that a gesture can be attributed to a specific artist at a precise moment in their practice. Archives do not preserve images alone; they trace continuities and ruptures within a creative trajectory. Provenance tells the story of how that gesture has been recognized, preserved, and transmitted.

In this sense, the market does not protect matter, but the act itself. It safeguards the possibility, for today’s viewer, of entering into direct contact with a gesture that belongs to the past yet continues to act in the present.

An invitation to slow looking

To recognize the gesture is to slow down. It means looking at an artwork not for what it represents, but for what had to happen for it to come into being. In a time dominated by speed and surface, the artistic gesture asks for attention, listening, and respect.

In the Journal of Luma Arte Contemporanea, this space is dedicated precisely to that purpose: restoring depth to looking, offering tools to read art beyond the image, and bringing back to the center what truly matters—the intentional act that transforms matter into an artwork.

This text is part of a broader line of reflection on the language of art and the construction of meaning in contemporary works. To further explore these themes, readers are invited to revisit the previous Journal article, which serves as its natural point of departure.

If you wish to explore these themes through historically grounded works and artworks available through the gallery, we invite you to explore the curated selections of Luma Arte Contemporanea.

Each artwork is a gesture that continues to speak—it is up to us to learn how to listen.