Quando pensiamo a chi sia davvero “universale” nell’arte, non ci riferiamo alla grandezza storica, né all’importanza accademica. Ci chiediamo piuttosto: chi è capace di parlare a chiunque, senza spiegazioni, senza mediazioni, con una forza immediata che attraversa i secoli e i confini? Per noi la risposta si concentra in due nomi, apparentemente lontanissimi: Caravaggio e Van Gogh.

Caravaggio porta in pittura il dramma della vita, con la stessa potenza con cui Shakespeare lo portava a teatro. Le sue tele sono scene sospese, istanti rubati al destino, come il coltello che brilla nella “Cena in Emmaus” o la mano che cade pesante nella “Morte della Vergine”. Non c’è bisogno di conoscere i dogmi cattolici per comprendere quelle immagini: bastano la luce violenta, la tensione dei corpi, l’ombra che avvolge il volto. Chiunque, anche un osservatore del XXI secolo che non abbia mai letto una pagina di catechismo, percepisce l’umanità travolgente che Caravaggio mette sulla tela. È lo stesso linguaggio che usano oggi il cinema neorealista o il teatro di strada: l’immediatezza del reale che diventa universale.

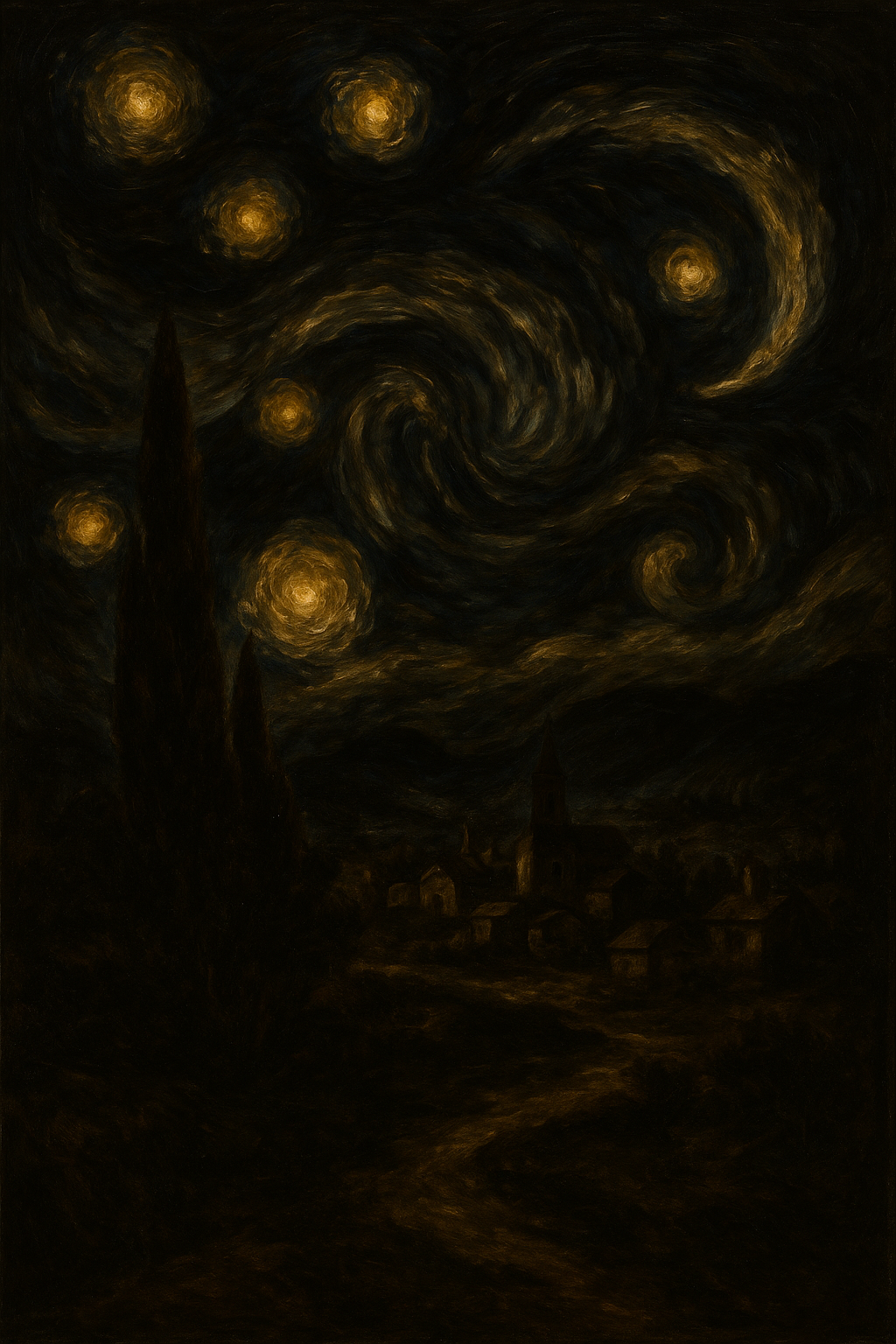

Van Gogh, invece, rovescia la prospettiva. Se Caravaggio parte dal reale per trasformarlo in dramma, Van Gogh parte dal sentire per trasformarlo in visione. Nei suoi cieli stellati, le spirali sembrano la trascrizione pittorica di un’emozione che appartiene a tutti: la meraviglia, l’inquietudine, il bisogno di infinito. Nei suoi campi di grano agitati dal vento ritroviamo la solitudine, la fragilità, la speranza. Il suo linguaggio è l’opposto del naturalismo: non mostra la realtà, ma la interiorizza e la restituisce amplificata. È lo stesso principio che muove la musica: non ci spiega il mondo, ce lo fa sentire. Ecco perché Van Gogh commuove chiunque, in qualunque parte del mondo.

Se proviamo a confrontarli con altri giganti, la differenza diventa evidente. Picasso è stato un rivoluzionario assoluto, ma la sua grandezza richiede un bagaglio di comprensione del cubismo, del rapporto con la tradizione e della sua frattura. Duchamp ha scardinato il concetto stesso di opera d’arte, ma senza conoscere il contesto dadaista un orinatoio resta solo un oggetto. Pollock ha aperto spazi sconfinati con l’action painting, ma non tutti sanno leggere la portata di quel gesto apparentemente caotico. Perfino Michelangelo e Leonardo, pur essendo universali per molti, restano legati a un immaginario rinascimentale che richiede una certa alfabetizzazione culturale.

Caravaggio e Van Gogh, invece, saltano ogni mediazione. Non hanno bisogno di codici. La loro lingua è quella delle emozioni primarie: dolore, speranza, rabbia, luce, disperazione, gioia. È la stessa lingua con cui l’uomo delle caverne tracciava un bisonte sul muro, o con cui oggi un regista come Tarkovskij o Wong Kar-wai riesce a parlare a spettatori di culture diversissime. È un linguaggio archetipico, che funziona perché non appartiene a un’epoca o a una scuola, ma all’ essere umano.

Interessante anche notare come siano diventati icone popolari oltre i musei. Caravaggio, per secoli dimenticato, oggi è un nome che attira folle nei musei come una star del cinema, capace di parlare tanto al critico quanto al visitatore che entra per curiosità. Van Gogh è forse l’artista più riprodotto al mondo: tazze, poster, borse, persino esperienze immersive digitali. Eppure, nonostante questa sovraesposizione, non perde autenticità. Non diventa mai un cliché vuoto, perché ogni volta che lo si guarda la sua pittura restituisce un’emozione autentica.

E allora la domanda resta aperta: chi sono, per voi, gli artisti universali?

È facile pensare a Monet e ai suoi ninfei, capaci di incantare chiunque, o a Klimt con i suoi ori avvolgenti. Alcuni direbbero che anche Warhol, con la sua Marilyn, appartenga a questa categoria. Ma c’è una differenza: Caravaggio e Van Gogh non sono semplicemente comprensibili o popolari, sono necessari. Rivelano qualcosa che ci appartiene in profondità, senza il filtro del tempo, della cultura o della critica.

Forse è per questo che, a distanza di secoli, restano due fari che orientano il nostro modo di guardare l’arte. Uno ci ricorda che la verità dell’uomo sta nella luce e nell’ombra che lo attraversano. L’altro che il mondo esterno non esiste senza quello interiore. Due poli lontani, eppure uniti dal dono più raro: l’universalità.

English

Universal languages in art

When we think of who is truly “universal” in art, we are not speaking about historical greatness or academic importance. We ask instead: who can speak to anyone, without explanations, without mediations, with a force so immediate it crosses centuries and borders? For us, the answer narrows down to two seemingly distant names: Caravaggio and Van Gogh.

Caravaggio brings the drama of life onto the canvas with the same force Shakespeare brought it to the stage. His paintings are suspended scenes, moments stolen from destiny, like the knife glinting in the “Supper at Emmaus” or the heavy hand in the “Death of the Virgin.” One does not need to know Catholic dogma to understand these images: the violent light, the tension of bodies, the shadow enveloping the face are enough. Even a viewer in the 21st century, with no catechism background, perceives the overwhelming humanity Caravaggio projects. It is the same language later found in Italian neorealism or street theatre: the immediacy of reality turned universal.

Van Gogh, on the other hand, reverses the approach. Where Caravaggio starts from reality to dramatize it, Van Gogh starts from inner feeling to transform it into vision. In his starry skies, the spirals look like painted transcriptions of emotions everyone knows: wonder, restlessness, the longing for infinity. In his wheat fields, shaken by wind, we sense loneliness, fragility, hope. His language is the opposite of naturalism: he does not show reality, he interiorizes it and returns it amplified. It is the same principle that drives music: it does not explain the world, it makes us feel it. This is why Van Gogh moves anyone, anywhere.

When compared with other giants, the difference becomes clear. Picasso was an absolute revolutionary, but his greatness requires an understanding of Cubism and its rupture with tradition. Duchamp dismantled the very concept of art, but without knowing Dada, a urinal remains just an object. Pollock opened boundless new space with action painting, but not everyone can read the magnitude behind the chaos. Even Michelangelo and Leonardo, though widely admired, remain tied to a Renaissance imagery that demands some cultural literacy.

Caravaggio and Van Gogh, instead, bypass all of this. They need no codes. Their language is that of primary emotions: pain, hope, anger, light, despair, joy. It is the same language used by prehistoric man painting a bison on cave walls, or by a filmmaker like Tarkovsky or Wong Kar-wai who speaks to audiences across cultures. It is archetypal, functioning because it belongs not to a school or period but to the human condition.

It is also telling how they became popular icons beyond museums. Caravaggio, forgotten for centuries, now draws crowds like a movie star, speaking equally to the critic and the casual visitor. Van Gogh is perhaps the most reproduced artist on earth: mugs, posters, immersive digital experiences. Yet despite this overexposure, his art never becomes hollow cliché. Each viewing still delivers an authentic emotion.

So the question remains: who are your universal artists?

Monet’s water lilies enchant almost anyone, Klimt’s golden embraces seduce effortlessly. Some would even include Warhol, with his Marilyns. But there is a difference: Caravaggio and Van Gogh are not just understandable or popular, they are necessary. They reveal something essential about us, bypassing time, culture, and criticism.

Perhaps this is why, centuries apart, they remain two guiding lights for how we see art. One reminds us that human truth lies in the interplay of light and shadow. The other that the outer world does not exist without the inner. Two distant poles, joined by the rarest gift: universality.